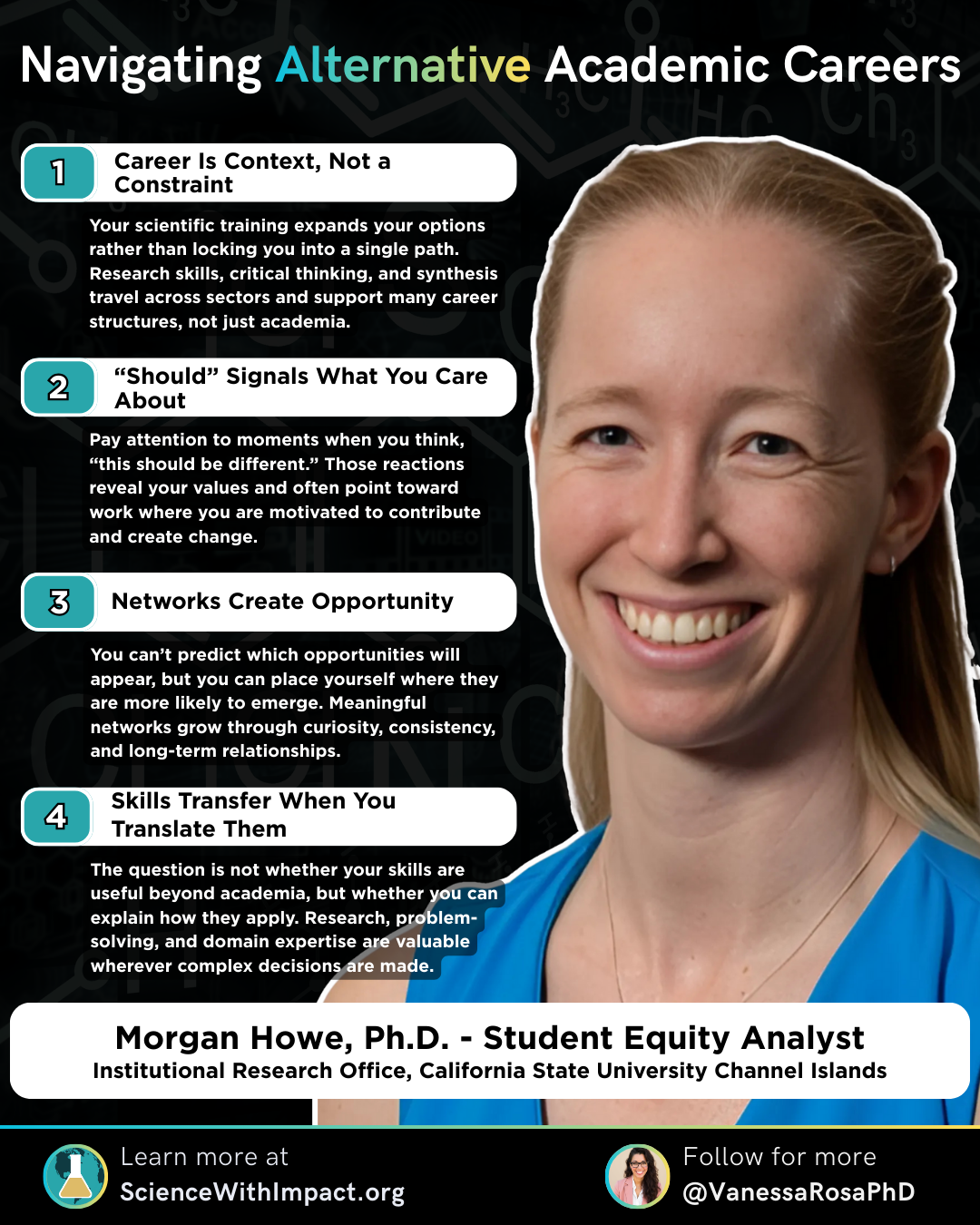

What if the most fulfilling version of your scientific career doesn't look like the one you were trained for?

Dr. Morgan Howe spent years following the traditional academic trajectory—earning a chemistry Ph.D., completing a postdoc in chemistry education research, building the skills expected of a future faculty member. Then she realized something critical: the career she was preparing for wasn't the life she wanted to live.

So she made a different choice. Instead of chasing tenure, Morgan pursued a role that would allow her to use her research expertise while also making space for ballet, baking, and boundaries. Instead of accepting that academic success requires sacrificing personal wellbeing, she found a position where leaving work at 5 PM isn't just acceptable—it's expected.

Her story offers a roadmap for STEM researchers navigating a question many of us face but few openly discuss: How do you build a meaningful career in science without letting that career consume your entire identity?

Meet Morgan Howe

Dr. Morgan Howe works as an institutional researcher at Cal State Channel Islands, jointly appointed between the Student Academic Success and Equity Initiative (SASE) office and the Institutional Research office. She applies her chemistry and chemistry education research expertise to data-driven equity work—the kind that actually changes systems.

What makes Morgan's story compelling isn't just that she left the tenure track. It's that she names the contradictions most researchers experience but rarely admit: the anxiety that came with teaching responsibilities, the relentless emotional labor of equity work, and the uncomfortable recognition that loving your research doesn't mean you'll love the career structures built around it.

"I wanted a career that was part of my life, not a career that was my life,"

Morgan explains. "I realized that I have a lot of other identities besides chemist or researcher. I'm a dancer. I'm a baker. I'm a friend. I am active. I am busy. I like to try new things. And those are all just as important to me as what I accomplish and what I am professionally."

This realization came gradually. During her first year of graduate school, a poorly taught organic synthesis course frustrated her enough that she sought campus counseling. When the therapist asked why bad teaching bothered her so deeply, Morgan's answer surprised even herself: "Because it should be better. I can do better. I want, oh, I want to do better. I care about teaching."

That insight redirected her toward chemistry education research. But the more significant pivot came later—recognizing that even within education research, the faculty path didn't align with the life she wanted to build.

Her current role demonstrates what alt-academic work can look like when it's done well. Morgan discovered that only 9 of 140 students who identified as Indigenous on applications were being counted in federal reports due to flawed reporting logic. She worked to fix that system. She does meaningful equity work, applies her analytical training to institutional problems, and still leaves at 5 PM for ballet class.

When her advisor lamented that "it's such a shame we're losing you," Morgan's response cuts to the heart of why the traditional narrative needs to change: "Nobody's losing me. I'm still here. I'm just putting my skills in a different place."

Finding Your Path: Decisions, Circumstances, and Self-Knowledge

Morgan's journey illustrates an important truth about career development that retrospective success stories often obscure: meaningful careers emerge from intentional decisions, fortunate circumstances, and evolving self-awareness combined.

"There's decisions and then there's circumstances or chances that happen," Morgan explains. "It used to frustrate me when people didn't speak about the chance part or when they did speak about the chance part, because I wanted to have control over that complete process."

Morgan's strategy involved deliberate networking at conferences—not because she naturally enjoys approaching strangers, but because she recognized it as necessary. She would review conference attendee lists beforehand, identify people working outside academia, and prepare questions to ask them. She attended talks even when the specific topic wasn't her research focus, because she never knew which conversation might open an unexpected door.

"I didn't know what happenstance it was going to be, but I made sure that I was present for as many happenstances as I could," she notes.

This approach requires specific self-knowledge: understanding what you value deeply enough to pursue it even when the path isn't clear. For Morgan, that clarity came from noticing her own reactions. When she encountered poor teaching or inequitable systems, her immediate thought was "this should be different." That persistent sense of "should" and "would"—as in "I would do this differently"—became a signal pointing toward work that mattered to her.

"It's something where I sit there thinking, this should, if I were doing it, I would, and that's one of the key identifiers for me," Morgan explains. "When I am thinking this about a topic, it means it's something I care about."

Understanding the Core Principle

Meaningful careers don't emerge from perfect planning or pure luck alone. They develop through three interconnected elements:

- Intentional decisions you make about how to position yourself

- Fortunate circumstances that arise unexpectedly

- Evolving self-awareness that helps you recognize what matters to you

You can't control which specific opportunities will appear, but you can position yourself to recognize and act on them when they do.

Step 1: Develop Strategic Self-Knowledge

Notice your "should" signals. Pay attention when you think "this should be different" or "I would do this differently". These reactions reveal where your values and interests align.

Track your reactions over time. Keep a running record of:

- Situations that frustrate you because they could be better

- Problems you find yourself wanting to solve

- Topics where you naturally think "I care about this"

Understand what you value deeply enough to pursue without a clear path. This kind of clarity helps you make decisions even when the outcome is uncertain.

Step 2: Position Yourself for Opportunities

Show up in relevant spaces. Attend conferences, workshops, and professional gatherings—even sessions outside your narrow focus.

Prepare for networking deliberately:

- Review attendee lists beforehand

- Identify people working in different contexts or sectors

- Prepare thoughtful questions to ask them

Be present for as many possibilities as you can. You won't know which conversation or event will matter, so maximize your exposure to potential opportunities.

Step 3: Accept What You Cannot Control

Let go of complete control. You cannot dictate which opportunities will emerge or when they'll appear.

Embrace the combination. Career development involves both decisions and circumstances. Frustration comes from wanting to control the entire process when you realistically can only control your positioning.

Trust the process. When you've positioned yourself thoughtfully and developed genuine self-knowledge, you'll be ready to recognize the right opportunity when it appears.

Putting It Into Practice

This framework works because it honors both agency and uncertainty. You take deliberate action while remaining open to unexpected paths. You develop clarity about what matters while acknowledging you can't predict exactly how it will unfold.

Start by identifying one "should" signal you've noticed recently, then take one action this month to position yourself in a space where related opportunities might emerge.

Translating Your Graduate Training

Pursuing an alt-academic career requires translating your graduate experiences into language that resonates with non-academic employers.

"When they're talking about team building, you can talk about collaborations and papers you've written with others," Morgan explains. "When they ask about problem solving, literally our entire job as graduate students... I remember thinking, well, of course I have problem solving skills. How do you think I got here?"

What seems obvious to you isn't always obvious to hiring managers from different backgrounds. Morgan's colleagues in institutional research often have degrees in sociology, higher education, or other social sciences. She had to spell out what her chemistry Ph.D. training actually involved.

"You have to pick all of that apart," she notes. "Be very explicit about how that appeared, because I promise you it did. You did all of those things in your graduate career. You just have to spell it out for people who have been in a different space."

This translation extends beyond technical skills to include less visible graduate work. Managing lab ordering systems? That's supply chain management and budgeting. Presenting at group meetings while preparing for conferences and TAing? That's managing multiple stakeholder demands and prioritizing competing deadlines. Mentoring undergraduates? That's supervision, training, and leadership development.

Recognize that "graduate student" isn't a universally understood job description. Different fields structure training in fundamentally different ways. Making your experiences legible to people outside your discipline isn't dumbing down your credentials—it's strategic communication.

Key Takeaways

Career Is Context: Your Training Creates Options, Not Obligations

Your scientific training doesn't lock you into a single career trajectory—it equips you with versatile capabilities that open many doors.

Morgan's story challenges a damaging assumption in graduate education: that a Ph.D. should lead to a faculty position, and any other path represents failure. This narrow framing traps talented researchers in feelings of inadequacy or guilt.

Her experience reveals a liberating truth. Your graduate training—research skills, analytical thinking, ability to synthesize complex information, capacity to learn new domains quickly—creates a foundation supporting many career structures. These capabilities are valuable across industry, government, nonprofits, consulting, policy, education, and institutional research.

The critical question isn't "Am I good enough for a faculty position?" but "Does this career structure align with how I want to live?" That reframing transforms career decisions from judgments about your worth into assessments of fit.

As Morgan says: "Nobody's losing me. I'm still here. I'm just putting my skills in a different place." The scientific enterprise gains professionals who bridge research and practice, translate findings into policy, improve educational systems, and advance scientific impact in ways traditional faculty roles don't always support.

"Should" Signals Commitment: Notice What You Think Needs to Change

Pay attention to the moments when you think "this should be different"—those reactions reveal where your values and interests align.

Morgan's response to poorly designed systems or ineffective teaching was a persistent sense that things should be better. That recurring "should"—and "I would do this differently"—became a reliable indicator of where her values, interests, and capabilities aligned.

This offers a practical career discernment tool. Instead of waiting for clarity about your calling, notice your reactions in real situations. When do you think "this should be different"? When does poor execution bother you enough that you want to improve it?

These reactions point toward work that matters to you, even before you've articulated why. They're signals worth following. Morgan's path from noticing poor teaching to chemistry education research to institutional equity followed a series of "shoulds" that gradually revealed coherence.

This approach distinguishes between work you find interesting and work you're committed to improving. Interest is passive; "should" is active. Interest observes; commitment wants change.

Networks Enable Serendipity: Position Yourself Where Opportunities Emerge

You can't predict or control which specific opportunities will appear, but you can deliberately show up in spaces where possibilities are likely to emerge.

Morgan's path involved both strategy and timing—"decisions and circumstances." She positioned herself by attending conferences (including sessions outside her focus), initiating conversations with people in different sectors, and staying present in professional communities.

Effective networking isn't about collecting contacts or optimizing profiles—it's about genuine curiosity. Ask thoughtful questions about others' work and maintain authentic connections. Show up mentally and physically present.

When opportunities emerge, you'll have the relationships and knowledge to act quickly. Morgan's job posting made sense because she'd already talked with institutional researchers at conferences. She understood the work and could articulate her fit because she'd learned about that path years before the opening appeared.

Strategic networking invests in future serendipity. You increase the probability that when the right opportunity appears, you'll be aware, prepared, and connected to people who can help.

Skills Are Transferable: The Challenge Is Translation, Not Capability

The challenge isn't whether you have valuable skills from graduate training—it's learning to articulate how those skills apply in different contexts and translate into the language employers outside academia understand.

Your research capabilities—designing studies, analyzing data, synthesizing information, communicating to diverse audiences, managing competing priorities, solving novel problems—are precisely what many employers need.

The barrier isn't capability; it's translation. "Stakeholder management" describes managing your advisor, committee, collaborators, and mentees. "Cross-functional collaboration" means coordinating with facilities, other labs, and diverse audiences. "Data-driven decision-making" is how you designed experiments and pivoted based on results.

Make these connections explicit. "Graduate student" isn't universally understood—training differs fundamentally across fields. Hiring managers need you to spell out what your training involved and what capabilities it developed.

Translating your experience isn't dumbing down credentials—it's strategic communication making your capabilities visible to those who need them. Your skills are valuable beyond academia; the work is helping others see what you can do.

Practical Guidance for Researchers Considering Alt-Academic Paths

Based on Morgan's experience, here are specific strategies for researchers exploring careers outside faculty positions:

Start with informational conversations

Identify people working in roles that sound interesting and ask them about their work. What does their typical day look like? How did they find their position? What skills from graduate training do they use most? What do they wish they'd known earlier?

Learn the language of job descriptions

When you encounter terms like "stakeholder management," "project leadership," or "data-driven decision making," practice articulating how your graduate work demonstrated those capabilities. Write these translations down—they'll be useful for cover letters and interviews.

Attend conferences strategically

Before attending, review the attendee list and identify people working outside academia. Set a goal to have meaningful conversations with 2-3 people doing work that interests you. Ask about their career paths and what skills they find most valuable.

Build a running list of your accomplishments

Don't wait until you're applying for jobs to document what you've done. Keep an ongoing record of projects you've managed, presentations you've given, collaborations you've contributed to, and problems you've solved. When you need to write application materials, you'll have concrete examples ready.

Recognize that career exploration is ongoing work

Morgan didn't figure out her path in a single revelation. It involved attending talks, having conversations, applying for various positions, getting rejected, trying again, and gradually clarifying what mattered most to her. Give yourself permission for that process to unfold over time.

Trust that your skills are transferable

The analytical thinking, problem-solving, communication abilities, and domain expertise you developed in graduate school are valuable in many contexts. The challenge isn't whether you have useful skills—it's learning to articulate how those skills apply in different settings.

Attend conferences strategically

Before attending, review the attendee list and identify people working outside academia. Set a goal to have meaningful conversations with 2-3 people doing work that interests you. Ask about their career paths and what skills they find most valuable.

Resources and Next Steps

If you're exploring alt-academic career paths, these organizations and resources can help:

- Professional networks: Many professional societies have committees or special interest groups focused on career diversity. These can connect you with people working in industry, government, nonprofits, and other sectors.

- Career development programs: Some universities offer workshops specifically for graduate students and postdocs considering non-academic careers. These can help with resume translation, interview preparation, and networking strategies.

- Informational interviews: Reach out to people working in roles that interest you. Most people are willing to have a 20-30 minute conversation about their career path if you approach them respectfully and come prepared with thoughtful questions.

Ready to Transform How You Communicate Science?

Thank you to Dr. Morgan Howe for sharing her honest reflections on building a fulfilling career in science that honors both professional expertise and personal wellbeing. Her story demonstrates that meaningful impact comes in many forms—including the quiet work of improving systems that directly affect students navigating higher education.

For researchers seeking to broaden their impacts, the pathway is clear: find artists who share genuine curiosity about your work, start small with proof-of-concept projects, build these collaborations into grant proposals from the beginning, and commit to long-term partnerships that allow deep exploration of connections between artistic and scientific concepts.

Thank you also to our listeners and readers who make impactful science possible.

Let's collaborate

Schedule a meeting with our founder, Dr. Rosa, to explore how we can help broaden your impact.

Learn More

1. Evidence-based impact measurement and communication.

2. Lasting national and local partnerships with STEM organizations.

3. Impact-centered professional development for students.

Member discussion