What happens when a composer with a polymer scientist father and piano teacher mother decides that music and science don't have to live in separate worlds? The answer is the Multiverse Concert Series—an innovative approach to science communication that's bringing audiences face-to-face with everything from Europa's hidden oceans to the molecular topology of polymer networks.

The Origin Story: Finding Purpose in the Intersection

David Ibbett didn't set out to become a science communicator. As a composer trained at the University of Birmingham, he followed the traditional path—until a NASA article about Jupiter's moon Europa sparked something different. "I was struck by this article from NASA about Jupiter's Moon Europa and the potential for microbial life beneath its crust and how there could be aliens within reach in our solar system," David recalls.

That inspiration led to his first major science-music integration: a tone poem for flute that imagined the sounds of alien life in Europa's subsurface ocean. "The flutes got to impersonate rocket sounds, they can do really good bubbling waters and imagined alien creatures that can kind of pretend to be an alien manatee at one point," he explains.

But the real turning point came when David moved to Boston 11 years ago and discovered an enthusiastic community of scientists eager to collaborate.

"I just found such enthusiasm in the community here for striking up these projects," he says. "A lot of scientists are just really excited to have a way to get their work out in an artistic form because they are passionate people."

That insight—that scientists need outlets for the emotions driving their research—became the foundation for Multiverse's approach. "The emotions are not part of that peer reviewed research and papers and articles," David notes. "Even though the emotions are often driving the reason that this work has happened."

Making the Invisible Visible: The Art of Polymers Project

David's five-year collaboration with the MONET Center for Polymer Research demonstrates how art can make molecular-level science intuitive. Working with researchers including Dr. Jeremiah Johnson and in partnership with Science with Impact's Dr. Vanessa Rosa, the project translates polymer chemistry into musical and interactive experiences.

"Any sort of curve could be a melody," David explains, describing how data from molecules being stretched and bonds breaking creates musical patterns. "You can see on the curve if you look at it as a graph, these moments where things snap and you get this sort of staircase effect."

Scientists: Dr. Rebekka Klausen and Sophie Melvin of Johns Hopkins, Dr. Jeremiah Johnson of MIT, Clara Troyano of MIT, Jafer Vakil of Duke University. Performers: Johnny Mok Cello, Dr. David Ibbett Piano/Electronics, Dr. Scott Barton Musical Robotics Compositions: Scott Barton, Amir Bitran, David Ibbett

But the project goes beyond passive listening. At the Cambridge Science Festival, David and his students unveiled an interactive game called "Musical Molecules" where participants read molecular structures like musical scores. "Each component of the molecule gets a different sound that represents the properties of that component. So a tight bond has a high tense sound or a flexible bond has more of a loose, lower sound," David describes.

The goal is to scale this experience: "We've tried with groups of three. We wanna try it with 300 next time all at once in the concert vault."

Active Music: Bringing People Together Through Science

David distinguishes between what he calls "active music"—music that brings communities together for a purpose—and music that becomes either overly cerebral or purely commodity-driven. "Music has a purpose in society," he emphasizes. "Have to find it and embrace it."

For Multiverse, that purpose is creating moments where people from across society experience science through emotional and sensory channels. "The feeling that you get when people from across society are brought together through music is such a powerful one," David reflects.

This philosophy shapes every Multiverse production. The Mars Symphony project, for instance, creates immersive soundscapes using actual audio from NASA's Perseverance rover and InSight lander. "We've taken the sounds from the perseverance rover, the Insight lander, and used those to create this Mars soundscape. But it goes onto the phones of every member of the audience," David explains.

Using spatial audio technology, the concert hall becomes Mars: "Each phone becomes a speaker and we can move dust devils around the room, we can have perseverance drive to the Jezero Crater across the room."

Measuring Impact: The ROSA Framework Applied

Measuring Impact: The ROSA Framework Applied

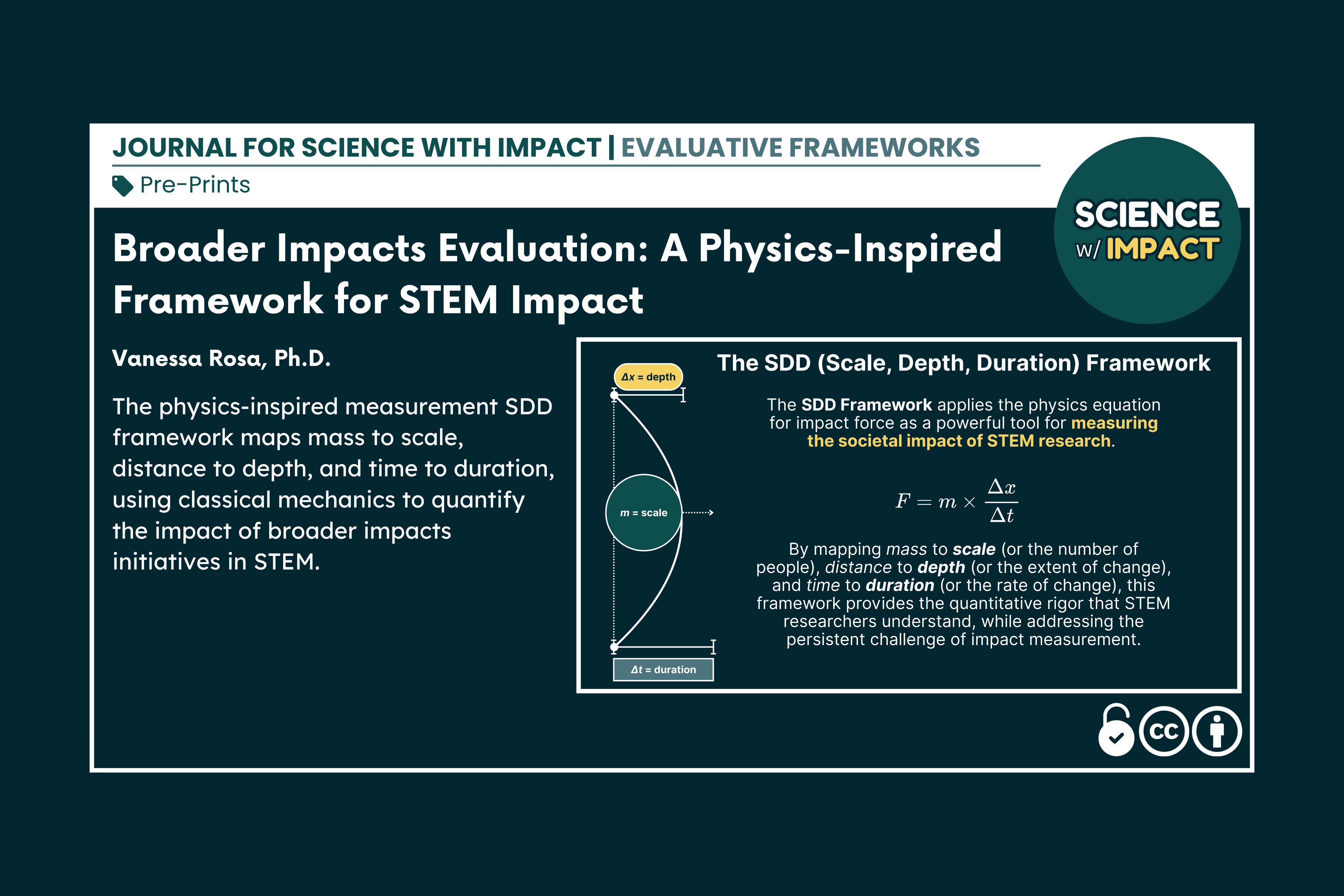

Using the ROSA evaluation framework from Science with Impact's toolkit, we can quantify the broader impacts of Multiverse's work:

Rate (Velocity of Change): From a single Europa-inspired piece to a full nonprofit producing multiple symphonies and concert series annually demonstrates accelerating production of science-art integration. The evolution from individual compositions to systematic collaboration models shows increasing velocity.

Outcome (Depth of Transformation): Multiverse doesn't just present science—it transforms how audiences experience and understand complex concepts. Participants move from passive listeners to active collaborators through interactive games and immersive technologies. Scientists gain new channels for expressing the emotional drivers of their research.

Scale (Reach and Scope): The work has expanded from single performances to touring productions, planetarium shows, and partnerships with institutions including NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and the MONET Center. The model is being explored for replication through other communities, inspired by the TEDx expansion approach.

Acceleration (Momentum and Sustainability): Long-term partnerships like the five-year MONET collaboration provide sustainable infrastructure. The development of replicable formats (concert companions, interactive games, spatial audio experiences) creates transferable models that can accelerate adoption across disciplines and institutions.

Key Strategies for Artist-Scientist Collaboration

Find the Right Match

David's advice for researchers seeking artistic collaborations is straightforward: "Work with an artist, create a public event experience." But he acknowledges the challenge: "You have to find the right one or the right team."

The key is discovering genuine connections between the art form and the science. "These connections are all there to be discovered," David notes, citing examples from cellular biology to exoplanet research. With polymers, the team found analogies between molecular networks and orchestral interweaving. With exoplanets, light spectra became musical harmonies.

Embrace the Emotional Dimension

Scientists often struggle to communicate why their work matters beyond technical details. David sees this as art's essential role: "You work on one small piece of the tapestry of life and chemistry, but you think with that piece of the puzzle, we can build a better world. Those are the kinds of feelings that are driving scientists, and if they don't have a way to get that out easily, it's the whole reason we have art to get these big feelings out."

The most successful collaborations happen when scientists are willing to share not just their data, but their passion and vision for how their work contributes to solving larger challenges.

Design for Discovery and Surprise

"Surprises are really important," David emphasizes. Every Multiverse production includes unexpected elements—whether it's spatial audio transforming a concert hall into Mars or interactive games where molecules become musical scores.

These surprises serve a purpose beyond entertainment: they mirror the experience of scientific discovery itself, creating "aha" moments that help audiences understand the excitement researchers feel when uncovering new knowledge.

Create Accessible Entry Points

Complex science requires careful scaffolding for public audiences. David's approach involves multiple layers: "Music and visuals. So either that's a wide screen video or planetarium projections." The combination of sensory modalities helps audiences grasp concepts that would be difficult through any single medium.

Interactive elements provide hands-on understanding: "People have to read the structure of a molecule like a little musical score. Each component of the molecule gets a different sound that represents the properties of that component."

Integrating Family and Passion

David's story also reveals how integrating family and career creates sustainable passion. Growing up with a polymer scientist father and musician mother, he experienced both worlds intimately. "Having parents who are true to their passion has left me with the resources that I need," he reflects.

Now a father of three—Arthur (1), Ellen (5), and Lawrence (8)—David finds ways to include his family in his work. His wife, a violinist, performs in the Multiverse ensemble. His son Lawrence will attend the Mars Symphony performance at JPL, getting a behind-the-scenes tour of the lab.

"It's great when you can find ways to integrate your family into your career work," David notes, acknowledging the challenges of balancing young children with demanding creative and professional work.

Navigating the Challenges of Science-Art Work

David is candid about the difficulties of sustaining science-art projects. "What we do is not an online platform," he notes. "You can just, if you post a really successful concert online no one's gonna watch it unless you make them watch it."

The work requires continuous effort in finding funding partners, building audiences, and maintaining momentum. "I'm basically trying to keep multiverse the right level of busy the whole time," David explains. Long-term partnerships like MONET have been essential: "MONET has been such a great one 'cause we have this long period of time and we're written into the outreach portion on the grant, which lets us do so much."

For scientists considering similar collaborations, this highlights the importance of building artist partnerships into grant proposals from the beginning, rather than treating them as afterthoughts or one-off events.

Key Takeaways for Bridging Science and Art

Emotion Drives Impact

Scientists' passion fuels their research, yet gets stripped from formal communication.

Art provides the missing channel for emotional expression that makes science relatable and compelling. David discovered that researchers are "looking for ways to share that aspect of the science as well, which makes the science so much more relatable and helps non-scientists understand why it's happening in the first place." When audiences connect emotionally to why research matters, they engage more deeply with complex concepts.

Collaboration Reveals Hidden Connections

Musical patterns exist in molecular data; exoplanet light spectra create harmonies.

Working across disciplines uncovers unexpected analogies that make abstract concepts intuitive. "These connections are all there to be discovered," David notes, whether it's polymer networks behaving like orchestral layering or gravitational waves sharing properties with sound. The key is bringing together collaborators willing to explore these intersections authentically rather than superficially.

Immersion Transforms Understanding

Transform concert halls into Mars; turn molecular structures into playable scores.

Multi-sensory, interactive experiences help audiences grasp complexity that lectures cannot convey. David's spatial audio Mars soundscape and Musical Molecules game demonstrate that when people actively participate in experiencing scientific concepts through multiple senses, abstract ideas become tangible. "Surprises are really important," David emphasizes—the unexpected moments that mirror scientific discovery itself.

Build Partnerships from the Start

Long-term collaborations create sustainable infrastructure for science-art work.

The most successful approach is writing artist partnerships directly into grant proposals' broader impacts sections from the outset. This transforms collaborations from one-off events into multi-year programs that can evolve and deepen. As David notes about the MONET partnership: "We have this long period of time and we're written into the outreach portion on the grant, which lets us do so much." This structural integration provides the time and resources needed to develop sophisticated translation methods—like the Musical Molecules game or Mars soundscapes—that wouldn't be possible with single-event budgets.

Conclusion: The Future of Science Communication Is Multisensory

Professor David Ibbett's work with the Multiverse Concert Series reveals a powerful truth: the most effective science communication happens when we stop treating art and science as separate domains and instead recognize them as complementary ways of understanding our world. By transforming polymer networks into orchestral scores, Mars rover data into spatial soundscapes, and molecular structures into interactive games, David demonstrates that complex research becomes not just accessible but emotionally resonant when experienced through multiple senses.

For researchers and science communicators, the path forward is clear. Seek out artists who share genuine curiosity about your work. Start small with proof-of-concept events. Build these partnerships into grant proposals from the beginning. Commit to long-term collaborations that allow deep exploration of the connections between artistic and scientific concepts. Most importantly, embrace the emotional dimension of your research—the passion and vision that drives your work but rarely makes it into peer-reviewed publications.

The barriers between disciplines are more permeable than traditional academic structures suggest. When scientists and artists collaborate authentically, the result isn't just prettier presentations—it's fundamentally new ways of helping society understand and engage with research that shapes our future.

As David and the Multiverse team continue expanding their model nationally and internationally, they're not just creating memorable concerts—they're building infrastructure for a new kind of science communication that prioritizes emotional connection, immersive experience, and community engagement. The future they're creating is one where scientific discovery and artistic expression work together to inspire wonder and understanding across all of society.

Resources for Implementation

The following programs and initiatives demonstrate successful models for broadening participation in STEM:

- SACNAS Leadership Programs: The Society for Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science provides leadership development through the Linton-Poodry SACNAS Leadership Institute (LPSLI), where Checo and Vanessa connected. Learn more about LPSLI cohorts

- SFS Emerge Program: The Society for Freshwater Science's federally-funded initiative supporting graduate students and early career professionals in aquatic science. Visit the Emerge website

- SFS Instars Mentoring Program: The original conference-based program that evolved into Emerge, still supporting undergraduate participation in freshwater science. Explore the Instars program

- RESCoPE: Research Experiences in the Southeastern Coastal Plain Environment, Georgia Southern's program connecting students with coastal plain science opportunities. Learn about RESCoPE

- MROC2S: Mentoring Research Opportunities in Coastal and Computing Sciences, Georgia Southern's interdisciplinary post-baccalaureate program. Explore MROC2S-RAMP

Ready to Transform How You Communicate Science?

Professor David Ibbett's journey from composer to science communication innovator demonstrates that the barriers between art and science are more permeable than traditional academic structures suggest. His work with Multiverse proves that when scientists and artists collaborate authentically, the result isn't just prettier presentations—it's fundamentally new ways of helping society understand and engage with complex research.

For researchers seeking to broaden their impacts, the pathway is clear: find artists who share genuine curiosity about your work, start small with proof-of-concept projects, build these collaborations into grant proposals from the beginning, and commit to long-term partnerships that allow deep exploration of connections between artistic and scientific concepts.

Thank you to Professor David Ibbett for sharing his inspiring journey and practical insights on bridging science and art. Your commitment to creating "active music" that brings communities together around scientific questions demonstrates what becomes possible when we refuse to accept artificial boundaries between disciplines.

Thank you also to our listeners and readers who make impactful science possible.

Let's collaborate

Schedule a meeting with our founder, Dr. Rosa, to explore how we can help broaden your impact.

Learn More

1. Evidence-based impact measurement and communication.

2. Lasting national and local partnerships with STEM organizations.

3. Impact-centered professional development for students.

Member discussion